The Politics of Time

Political Temporalities and Future Possibilities

Stefan Eich, “Expedience and Experimentation: John Maynard Keynes and the Politics of Time,” American Journal of Political Science (January 2025). [pdf]

Abstract: John Maynard Keynes is often seen as the quintessential thinker of the short run, calling on us to focus our intellectual and material resources on the present. This poses an intriguing puzzle in light of Keynes's own influential speculations about the future. I use this seeming tension as an opening into Keynes's politics of time, both as a crucial dimension of his political thought and a contribution to debates about political temporality and intertemporal choice. Keynes's insistence on radical uncertainty translated into a skepticism toward intertemporal calculus as not only morally objectionable but also at risk of undermining actual future possibilities. Instead of either myopic presentism or calculated futurity, Keynes advocated bold experimentation in the present to open up new possibilities for an uncertain future. This points to the need to grapple with how to align multiple overlapping time horizons while appreciating the performativity of competing conceptions of the future.

Excerpt: What had functioned in Burke as a critique of eighteenth-century French revolutionary millenarianism became in Keynes’s hands a critique of the equilibrium analysis offered by neoclassical economics. As Keynes delighted in pointing out, in so far as orthodox economists (a group that had not long ago included Keynes himself) demanded interwar austerity based on the long-run extrapolations of neoclassical economics, they ironically mirrored the French Revolutionaries in demanding sacrifices in the present in the name of supposed benefits in the future. Economic austerity sacrificed the present on the altar of an uncertain future. Paradoxically, then, the economic policies of the Conservative Party were, according to Keynes, based on a Jacobin philosophy of history.

The Political Thought of John Maynard Keynes

As a continuation of my research on the political theory of money, I am currently working on a book-length project on John Maynard Keynes’s political thought, based on his extensive political writings, his scattered theoretical reflections on politics, and his engagement with the history of economic and political thought. Keynes is today rarely, if ever, recognized for his political thought. He is more likely to be invoked as an adjective ("Keynesian”) that vaguely gestures toward either fiscal stimulus or the postwar welfare state. Both reductions are deeply misleading. Keynes was not just one of the most influential economists of the twentieth century, he was also an eloquent political commentator, an active political campaigner, and a perceptive theorist of domestic and international politics. My book reconstructs this much misunderstood political dimension and introduces political theorists to Keynes as an under-appreciated political thinker, emphasizing in particular his engagement with the politics of time and the problem of global economic governance at the dusk of empire.

I am also currently working on a blue book for the Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought that will bring together Keynes’s published and unpublished political writings.

Some recent work from this project:

Stefan Eich, “Keynes’ Ökonomie von Überfluss und Freiheit,” Surplus. Das Wirtschaftsmagazin (April 2025). [pdf]

Für John Maynard Keynes sollte wirtschaftliches Wachstum das moralische und politische Leben verändern. Seine Ökonomik war so widersprüchlich wie produktiv.

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) war ein Mensch der produktiven Widersprüche: ein Finanzinvestor, der das Streben nach Reichtum verachtete, ein Theoretiker der Freizeit, der sich zu Tode arbeitete, und ein Ökonom, der sich ein Ende seiner eigenen Disziplin erhoffte. Für Keynes war die Ökonomie weder eine Disziplin noch eine Methode. Stattdessen verkörperte sie für ihn eine Denkart, a way of thinking. … Im Gegensatz sowohl zu neoklassischen Ökonomen als auch späteren Keynesianern und Neo-Keynesianern, die alle die Knappheit als existenzielle Bedingung unendlicher menschlicher Wünsche naturalisierten, vertrat Keynes noch die optimistische Auffassung, dass die Aufgabe der Ökonomie in der Lösung des uralten Problems liegt, wie endliche menschlichen Bedürfnisse (im Gegensatz zu unendlichen Wünschen) befriedigt werden können. Um dieses wirtschaftliche Problem zu lösen, ist die Wirtschaftswissenschaft unerlässlich und absolut zentral. Aber sobald das Problem gelöst sei, spekulierte Keynes, wartet auf künftige Generationen eine in dieser Breite noch nie dagewesene Wertschätzung der »Lebenskunst«.

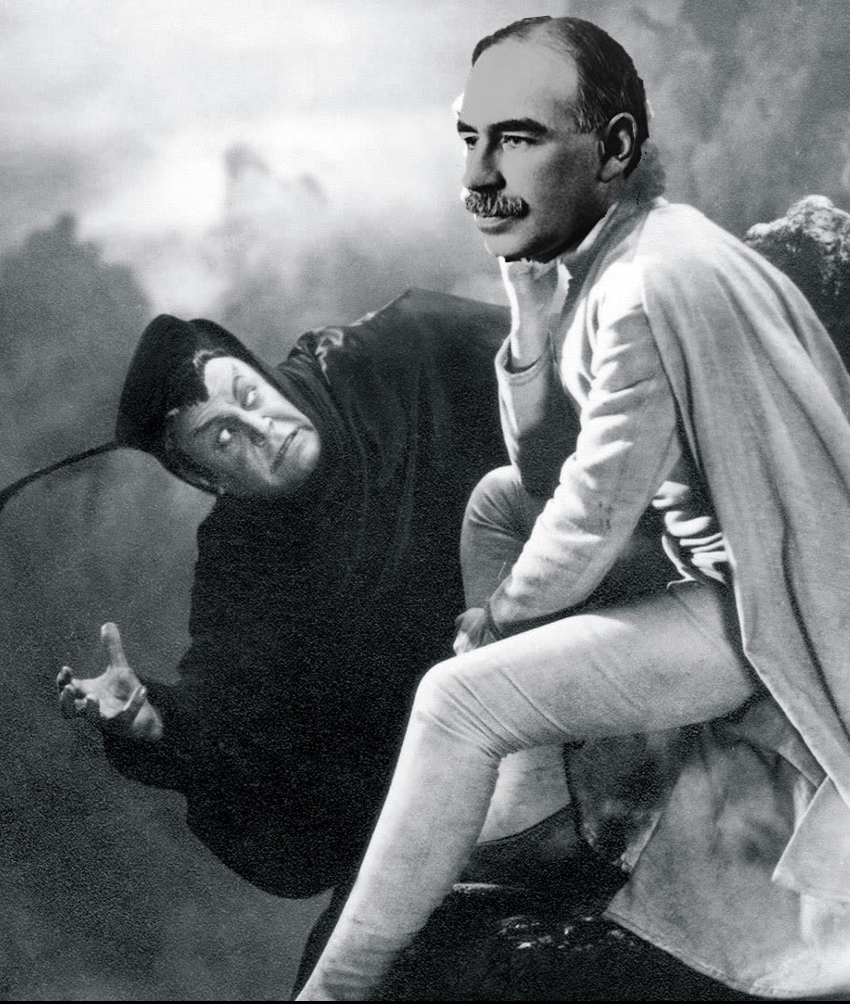

Adapted from F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926)

Stefan Eich, “Mephistopheles in the Anthropocene: Keynes’s Faustian Bargain and the Politics of Green Growth,” in Marion Fourcade, Greta Krippner, and Sarah Quinn (eds.), Political Economy, Rebooted (Duke University Press 2026).

Abstract: Today, Keynes is once more frequently invoked under the heroic guise of Green Keynesianism. In contrast to this simplistic invocation of him as a savior figure, it is worth recovering the ways in which Keynes grappled with a profound dilemma of capitalism that we confront today in a particularly acute form with a green twist. By re-reading Keynes’s “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930) not as a prediction but an exercise of moral imagination and a work of speculative fiction that explores future possibilities beyond the confines of capitalism, there is much to be learned in shifting from Green Keynesianism to Keynes himself. Doing so allows us to replace the misleading certainties of Keynesianism with Keynes’s own much more ambivalent thought that speaks more productively to the dilemmas of our present. This version of Keynes is at the same time no less troubling, as I explore in this chapter through E.F. Schumacher’s influential critique. Our own impasse mirrors Keynes’s Faustian bargain in a number of curious and haunting ways. To be sure, Keynes’s reasons for imagining a world beyond perpetual growth were primarily ethical rather than ecological. The analogy is nonetheless striking, not least because Keynes insisted on the need to indulge the moral distortions of capitalism for just a little longer. The underlying stakes of this Anthropocene version of Keynes’s Faustian bargain have at the same time been further raised. And yet it is far from clear that we can afford to dismiss our Mephistopheles.

Working Papers and Work in Progress:

“Uncertain Experiments: Keynes and Dewey on Democracy and Uncertainty”

Abstract: This paper proposes that John Maynard Keynes’s reflections on the experimental character of democracy offer underexplored intellectual resources for those interested in the ambivalent role of uncertainty in his economic and political thought, but also for contemporary debates about the status of democracy and its ability to respond effectively to the growing uncertainties of our own time, especially in the context of climate politics. To tease out these themes, I place Keynes in conversation with a much better-known account of the experimental character of democracy as a system of institutionalized uncertainty, namely John Dewey, whose pragmatist conception of democratic experimentation parallels Keynes’s in a number of surprising ways. One possible upshot of this pairing is a re-invigorated and mutually complementary debate about the relation between democracy and political economy around the themes of uncertainty and experimentation.

“Beyond Repair: Democratic Time and Experimental Futures”

Abstract: Contemporary democratic theory has responded to ecological crises, historical injustice, and institutional breakdown by shifting from promissory accounts of progress toward reparative and care-based conceptions of democracy. While this turn is normatively compelling and necessary, on its own it risks consolidating a defensive temporal settlement, one oriented toward damage control rather than collective world-making. This article argues that democracy requires an additional temporal grammar of experimental futurity. Experimentalism names neither a return to teleological progress nor a technocratic faith in innovation, but a set of political practices through which democratic societies can act under conditions of radical uncertainty. Read in this way, democratic experimentation supplies a non-teleological, non-guaranteed account of progress compatible with recent critical reconstructions, while restoring an affirmative horizon to democratic agency without reviving discredited fantasies of mastery.

Keynes, Indian Money, and B.R. Ambedkar

Another part of the project relates Keynes’s discussion of Indian money to B.R. Ambedkar’s seminal critique of Keynes.

“The Problem of the Rupee,” The Cambridge Companion to Ambedkar, ed. Anupama Rao and Shailaja Paik (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

“In Ambedkar’s treatise on rupee, a clear-eyed vision,” The Indian Express (December 10, 2023).